Outstanding Female Artists At Art Basel Miami Beach

Having been attending Art Basel Miami Beach since 2004, I bear true witness to its ever-growing scale of fairs and continuous addition of artists. The newly renovated Conventional Center added a space, Meridian, on the second floor for larger scale art works. There is possibility to seeing it match the glory of the dazzling Unlimited in Basel. Following the theme of Latino, Asian and black artists in the past years, in this piece I’d like to focus on standout artworks by female artists during the art week in 2019.

Art Basel Miami Beach — Kathleen Ryan

When passing by Josh Lilley Gallery’s booth at the Conventional Center, I was both taken aback and fascinated by the heap of giant rotten fruits -- lemons, oranges, peaches, pears and cherries on a flat steel trailer. While I could not take my eyes away, I was forced to look at the grotesque in a different light --- the fuzzy mold colonies are made of glittering gemstone: deep emerald-green malachite and amazonite, dark orange baubles, iridescent opal, smoky and rose quartz, amethyst, and freshwater pearls, etc. In a strange yet natural way, the vivid colors of moldy fruits made by Kathleen Ryan reminded me of 17th-century Dutch painter’s overripe apricots and half eaten peaches. Does Ryan’s work symbolize excessive consumption, decadence, or unease beauty? Maybe all of them.

Kathleen Ryan, Pleasures Known, 2019, mixed media, 79x91x174 in, Miami Beach Conventional Center

Growing up in the sunshine state of California, Ryan has long been nursing a fondness for succulent fruit as shown in her early minimalist sculptures using savaged and handcrafted material. A cluster of oversized concrete grapes mottled in varying tones of gray in Bacchante (2015) series, intended to engender the fluidity of the substance and gravity. For Between Two Bodies (2017), she placed three small glazed ceramic oranges between two huge three-ton granite blocks, raising our heart beats to the delicate fruits that stand up to enormous weight. Diana (2017) and Miranda (2017) feature giant palm fruits made of rose quartz and green jade, protected by cast iron seedpods hanging from the ceiling. From Fountain of Youth (2018), the artist seems to start to go beyond of her usual minimal aesthetic: a heart-ship cast iron pod holds abundant colorful fresh fruits made of plastic with sequins, plastic beads and steel pins.

For this bad fruits series, Ryan craved and painted polystyrene foams as fruits in different decaying stages. It takes about two months or more for the artist to fabricate a massive beaded fruit sculpture, ranging between one and three feet in diameter. In doing so, Ryan becomes a successful conductor of a variety of sparkling gemstones in copious quantities. Its power lies not only in its massive size of spoiled fruits, but also the stark contrast between the useless and revolting subject matter and the luxurious and sparkling materials. Furthermore, the more expensive and valuable natural gems are used to depict, eloquently, the putrid moldy patches while the cheap manufactured glass beads are to represent the still intact overripe skin. As the artist said, “Though the mold is the decay, it’s the most alive part.” Indeed, the tension eludes an easy reconciliation.

Berna Reale

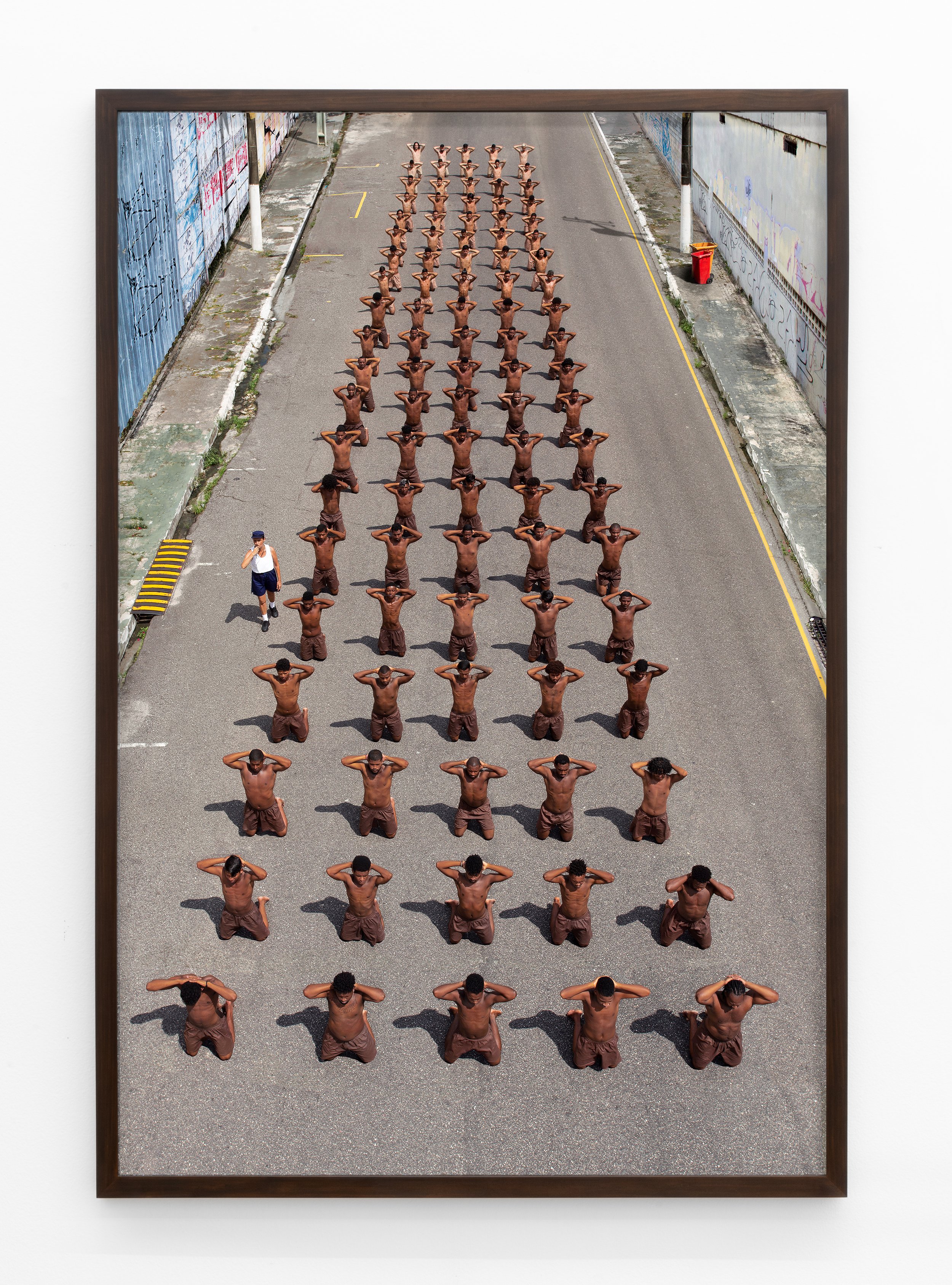

Among all the photos shown at the Conventional Center, Berna Reale’s Ginastica da pele (Skin Gymnastic, 2019) left a lasting impression with its visual power of submissive masculinity and racial division. In one photo, one hundred naked young men are on their knees in 5x20 parallel rows arranging from the darkest skin in the front to the few lightest skin at the far rear. Their heads are bent down to the ground and their hands folded behind their lower backs. In another photo, the same configuration of naked men stand on their knees with their hands behind their necks as if they are in mass incarceration. The artist, dressed in a uniform, is commending the movement of the young men, whose age is between 18 and 29 years old, representing the largest portion of the incarcerated population in Brazil. The gradation of skin tones is proportional to the data collected by INFOPEN in 2016: 67% are blacks and mixed race men who are often the target of the law enforcement. This powerful series addresses racial prejudice and the prison system crisis in the country.

Berna Reale, Ginastic da pele #5, 2019, mineral pigment on Premium Luster photographic paper, 59.1x39.4 in, Miami Beach Conventional Center

Berna Reale, one of the most important Brazilian artists, is a forensic expert for her hometown Belem police department since 2010. She is recognized for using her own body in fiercely provocative and raw performances, aiming to highlight social problems and denounce injustice in Brazil. Reale the artist and Reale the criminal scene investigator are a team in both fields. In her own words, forensic science makes her feeling more indebted toward the collectivity and more concerned with pressing social issues than before.

In Palomo (2012), the artist wears a dog muzzle on her face while riding Palomo, a white horse painted with blood red, commenting on the institutionalized abuse of power in Brazilian society. In Ordinario (Ordinary, 2013), the artist pushes a handcart loaded with anonymous bones of homicidal victims from the metropolitan area of her hometown. In Soledade (2013), she drives a golden Roman chariot pulled by pigs through a drug trafficking route in the outskirts of Belem. The police refused her request for protection as that neighborhood was off limits to them. She went through some trouble to find the boss who managed the area, and eventually was given a date and time for her performance.

In 2014, before the #MeToo and #TimesUp movements, Reale created a performance piece against sexual objectification and violence in Rosa Purpura (Purple Rose, 2014). Fifty women, including the artist, marched in protest in traditional Catholic schoolgirl uniforms except for their pink pleated skirts and the sex-doll prosthetic orifice in their mouths. As her critic said, “the strength of Berna Reale's imagery raises from the desire to get closer, countered by the sense of repulsion, a conflict that underlines the irony in Brazilian society's fascination for and disgust of violence.” Artists and artwork can’t really change the world, but to the viewers of their artwork, they might no longer the same.

Ginastica da pele (2019) took the artist about two years to prepare and finish, involving more than two hundred people. It is Reale’s most elaborate and important project in her career to date. In a way, I will say this piece is a transition for the artist from a self-performer of raw, explosive and sometimes masochistic to a conductor orchestrating a larger production with much more participants.

Untitled Fair --- Stephanie Syjuco

One of the most intriguing works in Untitled Miami Fair is Stephanie Syjuco’s conceptual piece The Visible Invisible(2018) at Gallery Catherine Clark’s booth: three faceless mannequins dressed in bright green traditional American dresses and hats made of green screen backdrop fabric. Chroma key is a visual effects technique commonly used in digital postproduction, allowing image or video editors to superimpose varying backgrounds like they do in futuristic films and superhero movies. And in the case of this work, the clothes could be replaced in editing, thus change their identities and stories. According to the artist, the three figures each wears a distinct style garment relate to America’s specific founding history, such as the Plymouth Pilgrim (at the expense of native people and their sovereignty), the democratic ideals of the American Revolution of 1776 (which granted citizenship to free white men) and the romanticism of Antebellum South (the seat of Confederacy and an economy based on slavery and white supremacy).

Stephanie Syjuco, The Visible Invisible Series, 2018, mixed media, Untitled Art Fair

These dresses are handmade by the artist and her team using simplified commercial patterns for theaters and Halloween costumes, drawing further attention to the distance between an authentic past and the convenient American narrative. In essence, the removable green-screen material operated as a projection screen for inaccurate narratives, exploring how American history itself has been manipulated and fabricated.

Syjuco, who is also an art professor, is known for creating thought-provoking, conceptual and participatory installations, often in the form of workshops and market exchange involving art students, young artists and audiences, exploring the tension between the authentic and the counterfeit, challenging ingrained assumptions about hierarchy of race, labor and income. She enacts a conflicted freedom of creation and aspiration, in which both autonomy and control try to make a point.

The artist has long been interested in the politics and history of economy and currency, the conflict between industry and craftsmanship, their relationship with globalization and capitalism. For example, Market Force (2015)is a seven-week research and then five-day collaborating silkscreen production, cut-and-assemble, sales event of fake currency and black market “goods” (watches, sunglasses, reebok sneakers, etc). At the installation opening, students were encouraged to purchase these black market items with their fake currency. Other fabricating workshop projects include creating stimulate marijuana out of common household ingredients (Ultimate Fabrication Challenge, 2013), false souvenirs of the Berlin Wall made from Soviet-era buildings and rubble in Poland(This is not Berlin Wall, 2014), fake currency proxies of the debts of people who make them (Debt Worth, 2018) or their desired life style (Money Factory, 2015).

The Visible Invisible (2018) in Untitled Fair highlights Syjuco’s tireless experiment with materializing the complexity of identities in flux. It examines how our historical narrative has rendered certain populations invisible, both literally and metaphorically. The invisible are women in this case, but they could be minorities, low-income population, LGBTQ or undocumented immigrants. It reminds us of the choices we make, and of those that are made for us.

The Margulies Collection --- Jennifer Steinkamp

The Margulies Collection installed an enthralling new media piece, Jennifer Steinkamp’s video projection Blind Eye 3 (2018) at its warehouse. Occupying an entire wall, the life-size birch trees cycle through seasons in a three-minute loop. The scars on the tree trunks cast a knowing gaze at the viewers, hence the title. Mesmerized by its sheer bright beauty, peace and invisible connection, I sat down to watch the trees swaying and bending in the pleasant breeze, their lush green leaves changing colors, falling to bare brunches, only to grow back again.

Jennifer Steinkamp, Blind Eye 3, 2018, video projection (color, silent), Margulies Family Collection

When Clark Art Institute invited the artist to make a project for its Tadao Ando designed building, Steinkamp noticed that the museum was surrounded by groves of birch trees. She did thorough research and looked into Gustav Klimt’s many birch paintings with specific details of the bark and knots on the trees. She was also fascinated by the recent discoveries that trees communicated through an underground chemical exchange and intimate web system of sharing information and nourishment. In turn, she wanted to create a piece in which the virtual trees are in a tight network and sentient by playing with the limitation of vision and how it affects perspective. The challenge was to erase the horizon line in order to create a different sense of depth through layering, speed and scale. Her birch trees are neither ultrarealistic nor obviously simulated, it is at a in-between state that makes viewers wonder.

Jennifer Steinkamp is acknowledged for using 3D animation and new media in her large-scale digital installations. “Blind Eye” was first shown in Clark Art Institute where she ran three projections simultaneously on three walls. Its narration has no end, but a continuous circle of life.

Bass Museum — Haegue Yang

During the art week, Bass Museum gave Korea artist Haegue Yang, who lives Between Seoul and Berlin, a solo exhibition occupying both the first and second floors. “In The Cone of Uncertainty” presented a selection of her works spanning the past decade. The title is originated from an expression of the South Florida vernacular about the predicted path of hurricanes, with which the artist addresses current anxieties about climate change, overpopulation and wasted resources.

Yang’s conceptually ambitious works are often inspired by various historical figures, their works or philosophy. She assembles complex industrial and simple daily objects through interactive, sonic and immersive experience with invoking light, wind and sound. Her interweaving narrations and reinterpretation focused on collapsing time and space while sifting through different geopolitical domains.

Haegue Yang, Yearning Melancholy Red, 2008/2019, Red Broken Mountainous Labyrinth, 2008, mixed media, Bass Museum

Central in one room is the juxtaposition of two large-scale installations, Yearning Melancholy Red (2008/2019) and Red Broken Mountainous Labyrinth (2008). The main material of both works are venetian blinds, but their distinct difference is the use of red color: one work consists of red blinds, while the other features white blinds colored by red light. Yearning Melancholy Red refers to Marguerite Duras (1914-1996), whose childhood was spent in French Indochina with her family in material and ethical desolation, casting outside by both natives and French colonizers. Only through the participation of the viewers by playing the drum set, did the fleeting red light move around the wall and blinds, adding playfulness and awareness to the intensity of the unspoken narratives.

Red Broken Mountainous Labyrinth tells a story of the chance encounter between Korean communist Jang Jirak (1905-1938), who is called Kim San in the book, and American journalist Helen Foster Snow (1907-1997) under the name Nym Wales. Together they wrote a book named Song of Ariran that later became one of the key texts for influencing and radicalizing labor movement activists in the 1980s in Korea. By staging the two works together, the artist suggested that we view history from new perspectives and find connections between the ever moving light, shadow and reflection.

Haegue Yang, Boxing Ballet, 2013/2015, mixed media, Bass Museum

Yang’s signature ‘Sonic Sculpture’ series Boxing Ballet (2013/2015) is inspired by Oskar Schlemmer’s performing art piece Triadic Ballet (1922). Schlemmer was an artist and Bauhaus professor who saw the modern world driven by two main currents, the mechanized (man as machine and the body as a mechanism) and the primordial impulses (the depths of creative urges). Triadic Ballet presented his ideas of choreographed geometry, in which men as dancers, transformed by geometric costume, moving in space like robots. Yang’s Boxing Ballet consists of six life-size figurine sculptures covered in golden bells, two hanging from the ceiling and the other four standing on casters along the spiral on the floor, reminiscent of a planetary orbit. Though these figurines do not dance ballet, if you push or pull them as you are welcome to do, they will wave or move, producing a quavering metallic sound from the bells.

Among many other pieces, the exhibition included some of Yang’s light sculpture series, Strange Fruits (2012-2013),taking the title from Abel Meeropol’s poem that expresses a American Jewish communist’s empathy for the horrors and tragedy of lynching in the South, made famous by Billie Holiday’s singing in 1939. While the lyrics do not mention lynching or dead human bodies, the metaphor is painfully clear. For her series, Yang intertwined string lights with colorful papier-mâché bowls and hands, and dangled them on the floor-standing metal clothing racks. The artist chose sentences of Meeropol’s poem to be the titles of each piece in the series, such as “For the Crows to Pluck”, “ For the Wind to Suck, For the Sun to Rot”, “The Bulging Eyes and the Twisted Mouth”. In turn, the hanging “fruits” are varied according to their titles.

Bass Museum --- Lara Favaretto

In Bass Museum, there was also an opening of Blind Spot, an exhibition by the Italian artist Lara Favaretto, featuring her paintings, sculpture and interactive installations that interweave narrative with form through dark humor and irreverence.

Your Money Here (2008) consists of a silver plaque with a slit, serving as a coin slot for charity that bears an engraving of Your Money Here, offering a cheeky commentary on philanthropy in the art world. If you insert a coin, it would disappear in the wall. Momentary Monument – The Library (2012-2019) presents a bookcase displaying 2,000 donated local books. The artist invites visitors to leaf through them and one might find the inserted pages from the artist’s own personal archive of her works.

Lara Favaretto, Gummo VI, 2019, Iron, car wash brushes and electrical motors, Bass Museum

The eye-catching piece of this show is the newly commissioned, site-specific work for Bass’ permanent collection,Gummo VI (2019). The kinetic installation comprises six enormous automated car wash brushes in bright color constantly twirling against one another or standing alone, each at a different speed, either becoming bigger and bigger, or wearing themselves down to a shriveled thin post. By taking industrial material from its natural environment and function, and rearranging its order and mechanism, the work alludes to the casualties of modern life that sometimes exhausts, changes or degrades.

Though her works often involve forces of decay, consumption and obsolescence, Favaretto resists inevitable loss by mobilizing and repurposing discarded items, recuperating old paintings and luggage, and recycling parts of her old works and outdated technologies.

I have seen many more noteworthy pieces by female artists during Art Basel Week, such as Jennifer Bartlett’s sculpture and painting combo installation Boats (1987) at Paula Cooper Gallery’s booth and Aki Sasamoto’s playful Past in a Future Tense (2019) series with spinning whiskey glasses blown by wind through duct systems. While gender never is a factor to define people’s talent and opportunity, as I realized that so many works that I loved in the fair were created by female artists, it becomes the focus of this review.